In this n+1-part series, we will be exploring how you can extend angr with new features, without editing angr itself!

angr is the popular framework for analyzing binary programs, from embedded firmware, to hardcore CTF challenges, all from the comfort of Python. angr’s roots lie in the Valgrind VEX instrumentation framework, meaning it benefits from the multi-architecture support and community maintenance. However, we live in a big world full of crazy things that aren’t Intel or ARM-based Linux machines.

What about microcontrollers?

What about Android bytecode?

What about Javascript?

What about BrainFuck??

(gasp! Not BrainFuck! Anything but BrainFuck!)

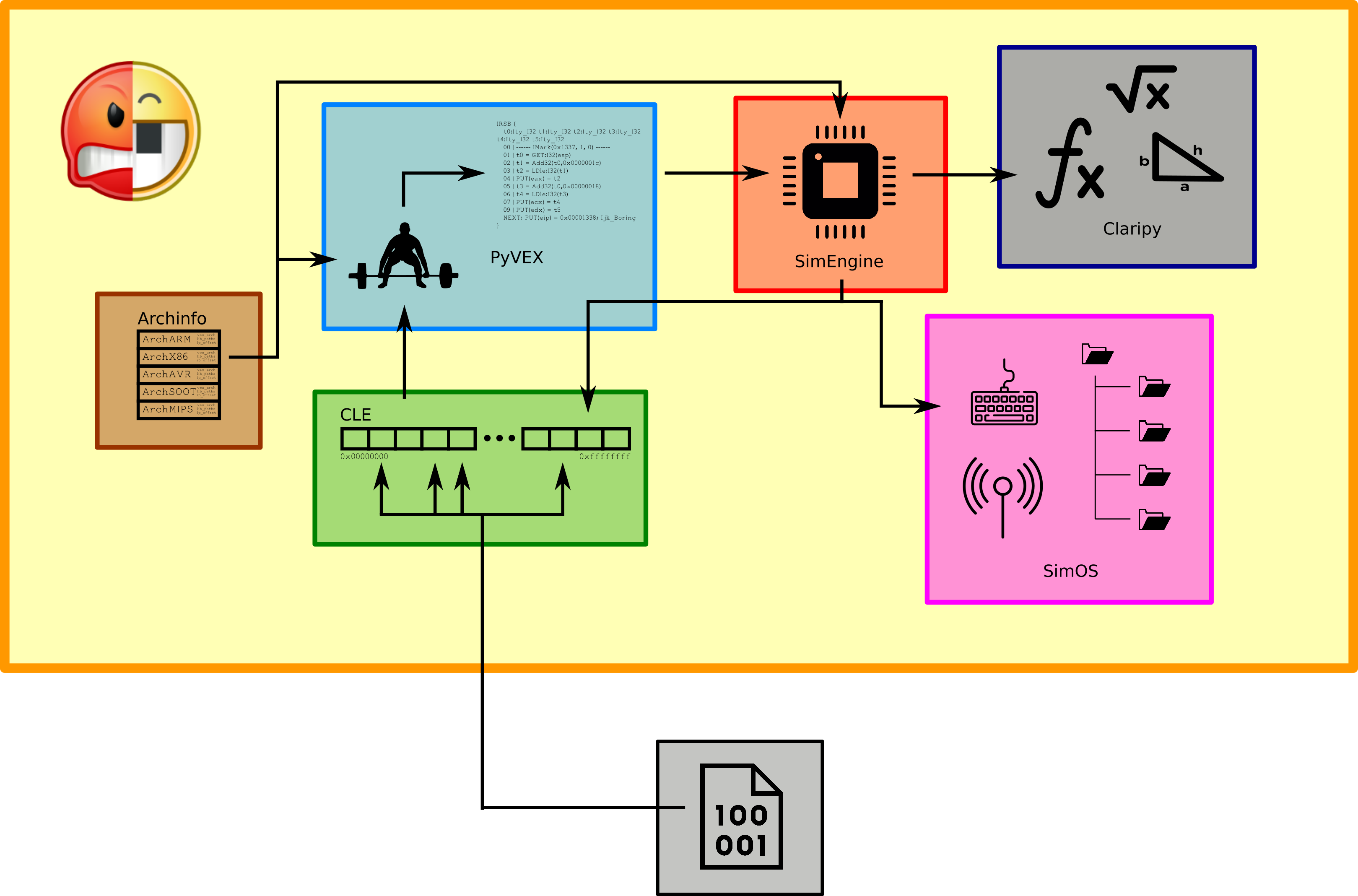

If you find yourself asking any of those sorts of questions, this is the guide for you! angr now supports extensions to each of its core components: the loader, architecture database, lifter, execution engine, and simulated OS layer. We will be exploring each in turn, with the goal of bringing the complete suite of powerful angr analyses to bear on a totally new class of program that it was not designed to before.

In order to not overcomplicate things, and make the core ideas clear, we’re going to start with something conceptually simple.

Sorry, that BrainFuck thing was not a joke. In this guide, we’re going to build the most insanely overkill BrainFuck analysis platform ever constructed. By the time you’re done here, you’ll be able to totally obliterate any of the Brainfuck crack-me programs that I hear may even actually exist.

First, let’s go over the components themselves, and how they fit together.

The angr lifecycle

If you’ve used angr before, you’ve probably done this: (blatantly stolen from angr-doc’s fauxware example)

import angr

p = angr.Project("crackme")

state = p.factory.entry_state()

sm = p.factory.simgr(state)

sm.step(until=lambda lpg: len(lpg.active) > 1)

input_0 = sm.active[0].posix.dumps(0)

That’s only a few lines, but there’s a whole lot going on here. In that little snippet, we load a binary, lift it from machine-code to an intermediate representation that we can reason about a bit more mathematically (VEX, by default), execute representation symbolically, and finally, print the input we needed to give the program to get to the first real branch, computed using a SMT-solver.

CLE, the loader

The first thing that happens when you create an angr project is angr has to figure out what the heck you just told it to load.

For this, it turns to the loader, CLE (CLE Loads Everythig) to come up with an educated guess, extract the executable code and data from whatever format it’s in, take a guess as what architecture it’s for, and create a representation of the program’s memory map as if the real loader had been used.

CLE supports a set of “backends” that service various formats, such as ELF, PE, and CGC.

For the common cases, this means loading an ELF, which brings with it the complicated mess of header parsing, library resolution, and strange memory layouts you both require and expect.

It also supports the exact opposite of this, pure binary blobs, with a backend that just takes the bytes and puts them in the right place in memory.

The result is a Loader object, which has the memory of the main program itself (Loader.main_object) and any libraries.

Archinfo, the architecture DB

During CLE’s loading, it takes a guess as to what architecture the program is for.

This is usually via either a header (as in ELFs) or some simple heuristic.

Either way, it makes a guess, and uses it to fetch an Arch object from the archinfo package corresponding to it.

This contains a map of the register file, bit width, usual endian-ness, and so on.

Literally everything else relies on this, as you can imagine.

SimEngine, the simulated executer

Next, angr will locate an execution engine capable of dealing with the code it just loaded. Engines are responsible for interpreting the code in some meaningful way. Fundamentally, they take a program’s state– a snapshot of the registers, memory, and so on– do some thing to it, usually a basic block’s worth of instructions, and produce a set of successors, coresponding to all the possible program states that can be reached by executing the current block. When branches are encountered, they collect constraints on the state which capture the conditions needed to take each path of the branch. In aggregate, this is what gives angr its reasoning power.

PyVEX, the lifter

angr’s default engine, SimEngineVEX, supports many architectures, simply because it doesn’t run on their machine code directly. It uses an intermediate representation, known as VEX, which machine code is translated (lifted) into. As an alternative to creating your own engine for a new architecture, if it is similar enough to a “normal” PC architecture, the faster solution is to simply create a Lifter for it, allowing SimEngineVEX to take care of the rest. We will explore both Lifters and Engines in this guide.

Claripy, the solver

Every action an engine performs, even something as simple as incrementing the program counter, is not necessarily an operation on a concrete value. The value could instead be a complicated expression, that when computed on, should actually result in an even bigger expression. Creating, composing, and eventually solving these is Claripy’s job. Claripy uses a SMT-solver, currently Microsoft’s Z3, to do all of this heavy-lifting. Thankfully, we won’t need to delve into that in this series, as SMT-solving is some serious black magic.

SimOS, the rest of the nasty bits

If we just view the engine’s work on a program from the states it provides, we’re going to have a lot of work to do to get anything useful out. Where is stdin? What the heck do I do with files? Network? Are you kidding? These higher-level abstractions are provided by the OS, and don’t exist at the bare machine level. Therefore, SimOS' job is to provide all of that to angr, so that it can be reasoned about without all the pain of interpreting just what the fake hardware would do. Based on a guess from CLE, a SimOS is created (ex. SimLinux), which defines the OS-specific embellishments on the initial state of the program, all its system calls, and convenient symbolic summaries of what syscalls and common library functions do, known as SimProcedures. These make angr dramatically faster and more compatible, as symbolically executing libc itself is, to say the least, insanely painful.

angr, the real deal

Finally, with a Loader, an Engine, an Arch, and a SimOS, we can get to work! All of this is packaged into a Project, and offered to the higher-level analyses, such as Control-flow Graph reconstruction, program slicing, and path-based reasoning, as in the earlier example.

In the next part, we’ll introduce our chosen architecture, BrainFuck, and discuss the implementation of additional architectures.

Image icons made by

- Freepik from Flaticon, licensed by CC 3.0 BY

- Smashicons from Flaticon, licensed by CC 3.0 BY

- computer

- clipground

- PinArt

tutorial

tutorial

subwire

subwire